The life of Krišjānis Barons covered an important period of time in the history of the Latvian nation ˗ from the age of indentured servitude until the beginning of the Latvian state. Krišjānis Barons cast a bridge from the new Latvian ideas that emerged in the mid-19th century about the nation’s sovereignty, education, equality and economic and cultural development so as not to disappear among large nations, to the Latvian liberation battles and the first years of the new Latvian state. Barons was an unbreakable link among generations and laid the spiritual foundations for Latvia’s future.

Krišjānis Barons

1835–1923

Galerija

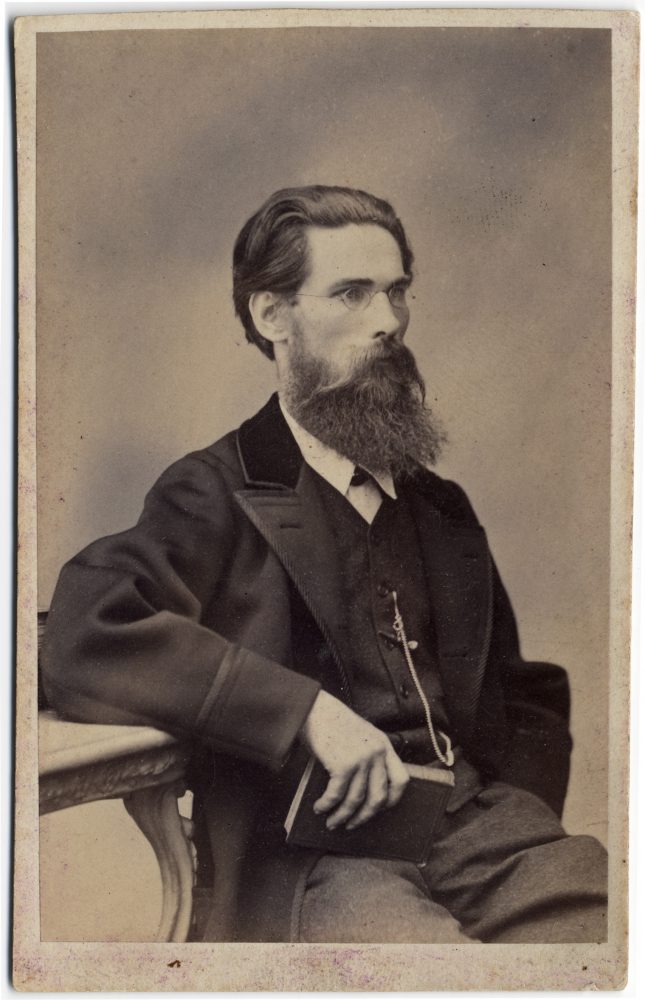

Krišjānis Barons was a folklorist, writer and publicist, as well as one of the most distinguished new Latvians and cultural workers. He was born on October 31, 1835, in Strutele. Barons studied at the Jelgava Gymnasium and then the university in Tartu, where he studied mathematics and astronomy. He and other Latvian students established a group at the university, and while he was still a student, he published his first articles in the newspaper “Mājas Viesis” (Home Guest). In 1859, while walking from Tartu to his home in Dundaga, Barons was inspired to write the first Baltic book about geography ˗ “Describing our Fatherland” (Mūsu tēvzemes aprakstīšana, 1859).

In 1861, at the invitation of his friends Krišjānis Valdemārs and Juris Alunāns, Barons moved to St Petersburg, where, in the summer of 1862, Valdemārs began to publish a weekly newspaper in Latvian ˗ Pēterburgas Avīzes (Newspapers of Petersburg). Barons became the newspaper’s editor. It was a diverse newspaper which published articles about economic, educational, legal, scientific and artistic issues. The central job was to popularise national ideas among Latvians. Barons and Valdemārs tried to use the newspaper to awaken, encourage, reveal and raise the self-confidence of the nation and to enhance practical knowledge. Barons published nearly 150 articles about astronomy, physics, geography, the natural sciences, technology and ethnography. In the area of linguist, he helped to improve Latvian orthography and introduced international concepts to scientific literature. Barons also published poetry, prose and satirical dialogues.

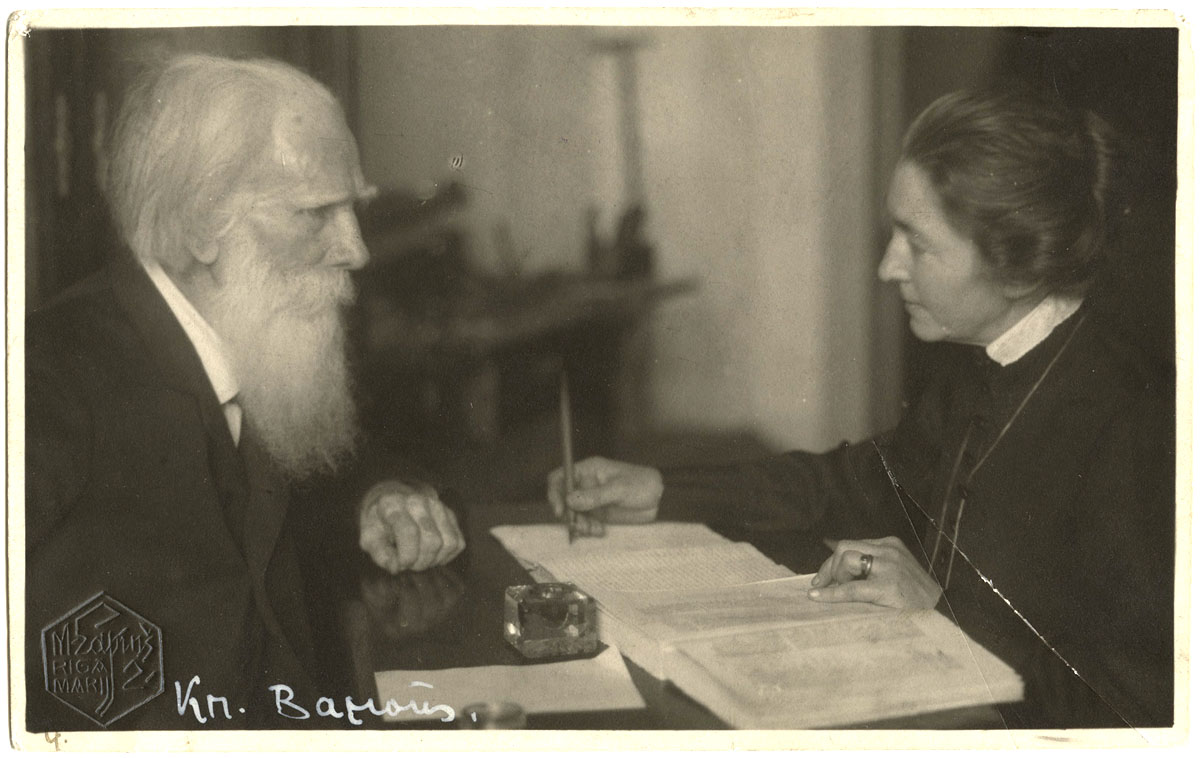

And yet the key achievement by Krišjānis Barons was that he collected, arranged, edited and published Latvian folksong quatrains known as the dainas. Fricis Brīvzemnieks started the work, but in 1878 Barons took it over. Between 1894 and 1915, he released six volumes of Latvju Dainas (Latvian Dainas), with 217,996 folksongs and an extensive introduction. Barons developed a system for the publication of the folksongs so as to consequentially cover human lives. Never has there been such a massive collection of folksongs, and the original cards on which Barons recorded the songs are held by the Archives of Latvian Folklore of the Institute of Literature, Folklore and Art of the University of Latvia.

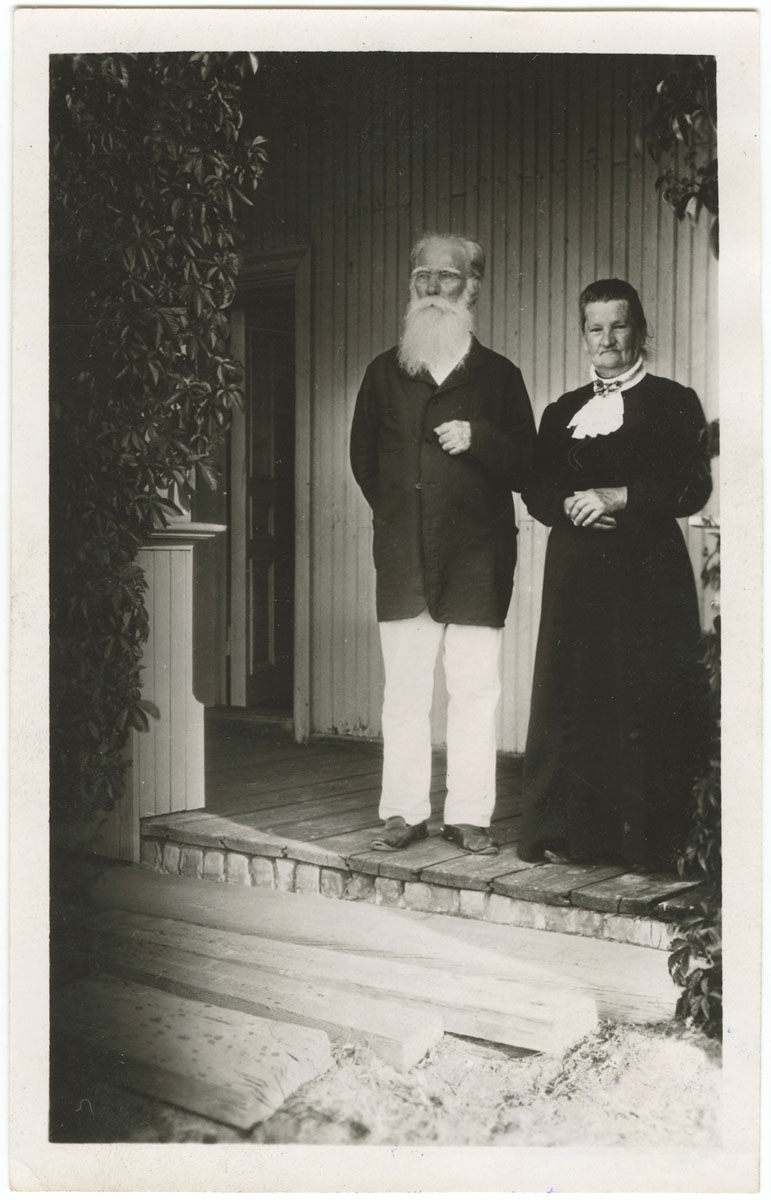

In 1919, Krišjānis Barons started to keep a journal in schoolchildren’s notebooks, on individual pieces of paper and often on the reverse side of envelopes. These memoirs ended suddenly when Barons was working as a home teacher in the family of Ivan Stankevich in Russia. First he was simply employee, but eventually the aristocrat and his employee found spiritual closeness. They had many common interests and a similar attitude about life. Ivan Stankevich’s heart had led him to marry a common girl, thus standing up against the ideas of his caste. Krišjānis Barons was not a radical, at least in public. He married Dārta Rudzīte, who was a servant girl with no education at all. She learned how to write down her name when she was an adult.

The systematisation of folksongs for Latvju Dainas, which became Barons’ main work in life, began at the aristocrat’s estate.

Krišjānis Barons’ life was always linked to powerful women. When he was a child, it was his mother, Eņgele, who, after the death of her husband, remained alone with a large brood of children. She taught her kids to be independent, moderate and frugal, and in later years those were described as the only characteristics for Barons. Life taught him to calculate everything, write things down and have a clear sense of finances. Arranging the folksongs was a voluntary process, and no one paid him for the work. A detailed list of all income and expenditures was essential for Barons when it came to his family budget.

The existence or non-existence of an educational document never led Krišjānis Barons to evaluate others. His wife, Dārta, had characteristics that she would never have learned at school. Those came from her heart. Dārta was a few years younger than her husband. She was born in Limbaži and was known as the little orphan girl, because she lost both of her parents at an early age. After spending years in Russia, Dārta was the one who undertook the job of getting in touch with Krišjānis’ relatives.

Dārta found support and felt that a strong family was a true treasure in life. She guarded her brood as best she could. A modern woman would not understand the extent to which Dārta served her husband. She was the ideal woman for him. Dārta was merry and loved being out in society, but her only goal in life was to pass her mission on to others. Her daughter-in-law Līna proved to be appropriate. Dārta and Līna were linked by a promise, and Dārta and Krišjānis were linked by work. Līna met this man when he was already elderly ˗ thoughtful, melancholic, sometimes incapable, but spiritually strong. Līna Barona was the third woman in Krišjānis Barons’ life, and it was she who became the most trustworthy nurturer of his memory.

Līna also supported her husband, Kārlis Barons. He was actively involved with the Rīga Latvian Society, where he held important posts. He published articles in the press about the natural sciences and aspects of medicine, and he delivered papers at the association. Līna helped him to write and translate them, because she spoke several languages.

World War I was challenging for the family. Kārlis Barons, Jr., was killed on the battlefield during Latvia’s independence battles before his 19th birthday. After the war, Līna became a true colleague of Krišjānis Barons in preparing the volumes of folksongs. After he died, she finished the fourth volume for publication and felt that a particularly important job was to publish his memoirs.

A portrait of Krišjānis Barons would be unimaginable without the people who were noticeably or imaginatively alongside him. They were all shapers of Barons’ life, influencing his nature, thinking, relationships and attitudes.