Ojārs Vācietis was one of the most brilliant Latvian poets during the latter half of the 20th century. Academician Jānis Stradiņš has called him “a great gift for a small nation,” and the poet Imants Ziedonis described Vācietis as “the conscience of the nation” and “the vertical of adaptation.” The poet’s work was aimed at eternity, and he was very much a prophet about the age in which he lived.

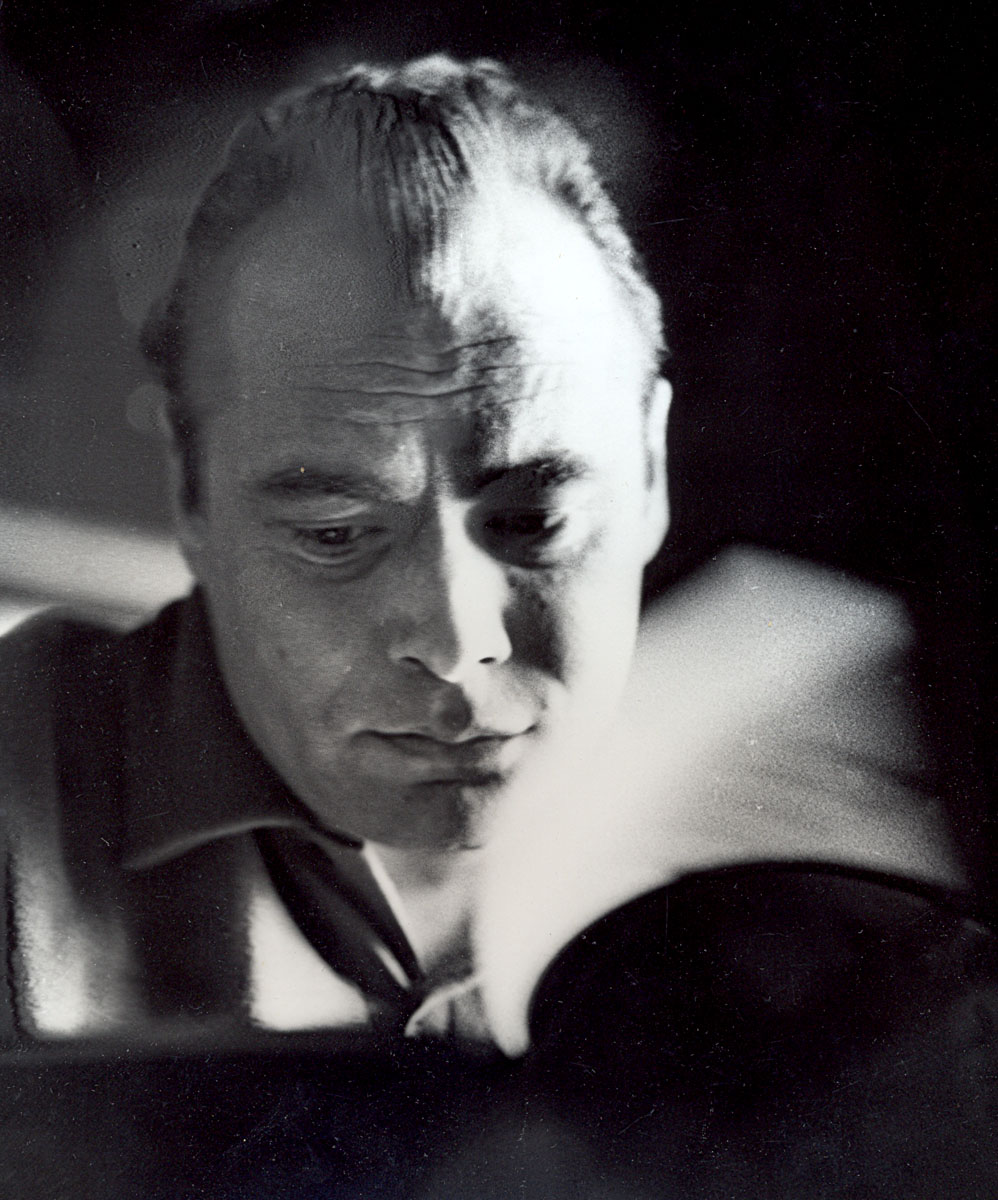

Ojārs Vācietis

1933–1983

Galerija

Ojārs Vācietis was born in Trapene in northern Vidzeme in 1933. World War II was an indelible component of his childhood, and for the rest of his life, Ojārs detested violence and supported life as the highest value. He attended high school in Gaujiena, and that is where he learned to love poetry and music. The most incalculable and beautiful river in Latvia, the Gauja, accompanied him throughout his life and until his burial in Carnikava. It seems that the restlessness of the Gauja is found in Ojārs’ first collection of poems, “The Wind of the Distant Roads” (Tālu ceļu vējš, 1956).

Ojārs Vācietis once wrote that the true centre of Europe was in Gaujiena, but beginning in January 1960, he lived in the heart of Rīga, which he had discovered ˗ in the Pārdaugava neighbourhood and alongside the Māra Pond. Until his death, the poet lived at Liela Altonava Street 19 (Ojārs Vācietis Street today). His wife, poet Ludmila Azarova, says that poetry appeared in her husband’s mind when he was wandering around the Āgenskalns neighbourhood, the narrow streets of Torņakalns, the jungle of bird cherry trees and nettles along the little Mārupīte River, the Māra Pond (which the poet called a lake), the trails of Zaķusala and Lucavsala islands, and the banks of the Daugava River from Bolderāja to Katlakalns. That is where Ojārs Vācietis experienced the presence of noble Latvians from the past. The cultural layer in Pārdaugava is thick, and Ojārs Vācietis created one part of it.

Vācietis released 12 collections of poems, four collections of poems for children, as well as a series of essays, reviews and publicist articles. He also translated many poems and books, and his translation of Mikhail Bulgakov’s “Master and Margarita” has been unsurpassed.

Ojārs Vācietis was never afraid of writing down what his heart told him, even though that often was in contradiction to the ruling nomenclature in Soviet Latvia. Sometimes his poems remained unpublished for a long time, and Soviet ideologists criticised him harshly. The ideologues could not hush up Ojārs’ talent, however. His word was too powerful, and the people loved him. The regime could only “punish” him with various honorary titles and premiums, but that didn’t help. Ojārs Vācietis never changed, and he rejected conjuncture. He wrote with open nerves as if he had no skin. Ojārs was open to all pains and joys.

The extraordinary talent, immeasurable love, maximal honesty and internal freedom allowed Ojārs Vācietis to become a legend. His poems were a source of strength. That is the same magical strength that exists in our folksongs and in the poems of Rainis and Čaks. Vācietis developed this further, and poetry was his only means for existence.