Contributors:

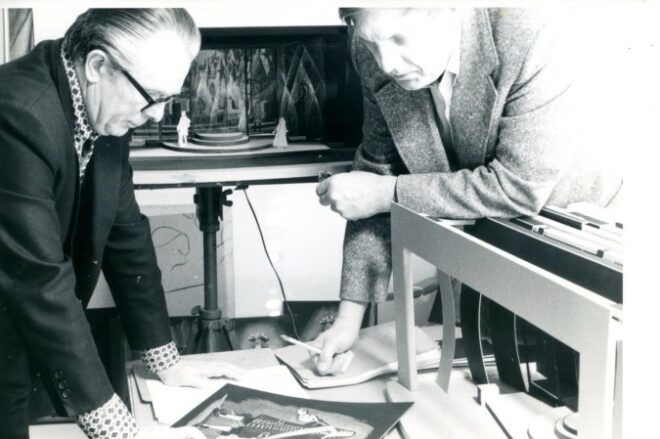

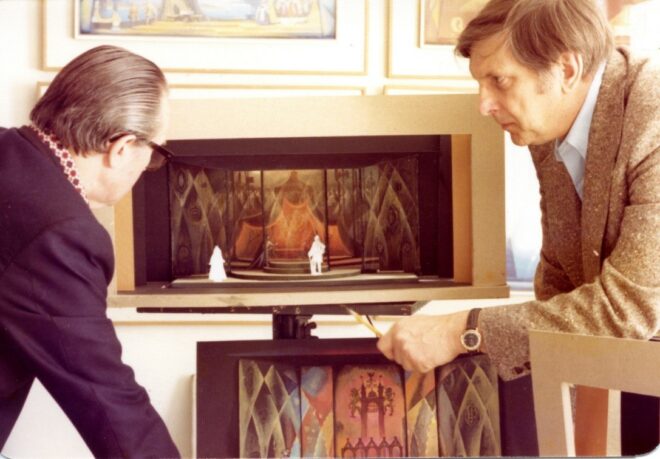

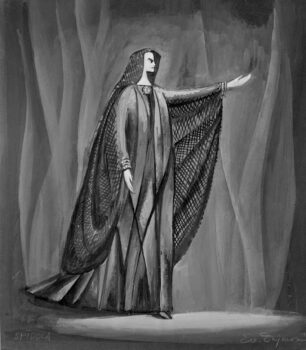

Pēteris Dajevskis: urban planner, exhibition consultant, anthropologist, and son of Evalds Dajevskis;

Astrīda Cīrule, specialist at the The Rainis and Aspazija Summer House;

Zane Grudule, Communications Specialist for the Association of Memorial Museums.

Materials for this digital interpretive experience come from the personal collection of Pēteris Dajevskis, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, US, and the collections of the Museum of Literature and Music, the Latvian War Museum, the National Library of Latvia, and the Andrejs Pumpurs museum in Lielvārde.