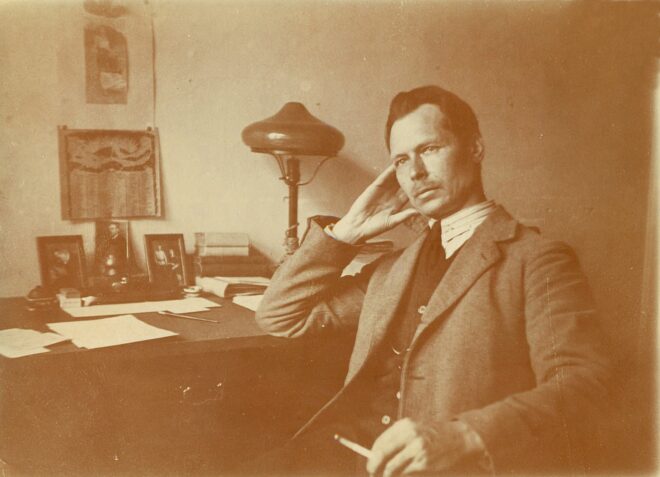

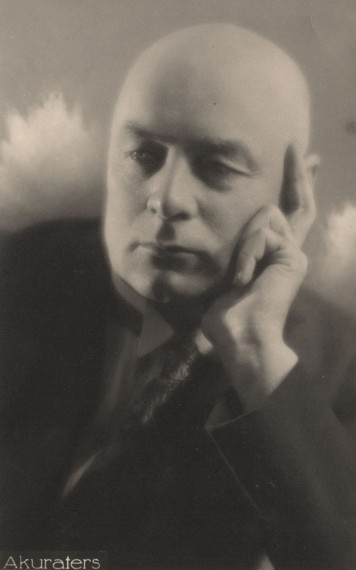

Jānis Akuraters enjoyed music not only at home and in concert halls in Riga, but also in the best European music houses and in the company of friends abroad.

There is a story involving the French anthem and the song of the Revolution, “Marseillaise”. It was sung in Finland in the autumn of 1907 by a member of Albert Traubergs’s group as a farewell to his comrades, the day before he committed his terrorist act, after which he was arrested and sentenced to death.

In a completely different vein, the Marseillaise was performed at the Elysée Palace in 1925, when Akuraters accompanied the Reiters Choir on a European tour, and the choir was invited to a reception by French President Pierre Paul-Henri Gaston Dumergue.